Interview with Two Contemporary Forest Owners: A New Form of Forestry to “Protect the Mountains”

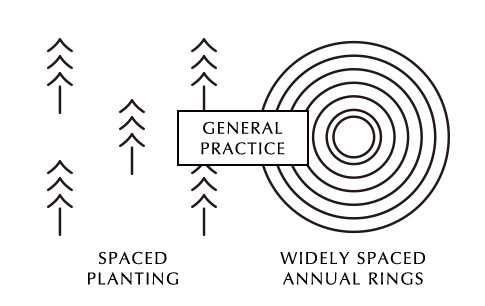

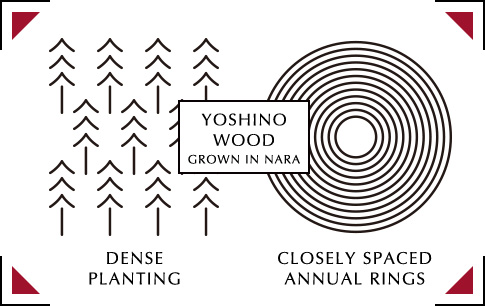

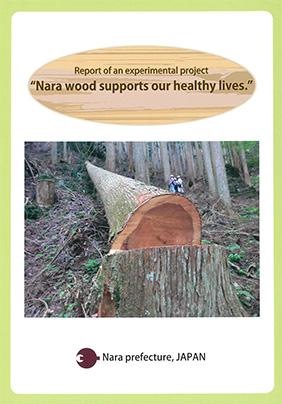

Yoshino cypress and Yoshino cedar—known for their beautiful color, minimal knots, and dense annual rings—have long been used in the construction of shrines and temples, and as material for sake barrels. In the Yoshino region of south-central Nara Prefecture, a distinctive silviculture—dense planting, frequent thinning, and long rotation periods—has produced this exceptional quality timber. The Shimotako district in Kawakami Village, Yoshino County, Nara Prefecture, known as the birthplace of Yoshino Forestry, is home to magnificent, towering trees said to have been planted during the Edo period. The beautiful, orderly rows of trees possess a majestic presence, fitting for one of the Three Great Man-Made Forests of Japan, clearly showing the long-term, painstaking care they received from human hands. However, this beautiful forest now faces a crisis: it might be lost. The demand for Yoshino timber has been declining since its peak during Japan's period of rapid economic growth (1950s–1970s), due to changes in residential construction styles. Today, the traditional forest management system—based on the partnership between the forest owner and the forest custodian—is on the brink of collapse due to a shortage of successors. We spoke with Kiyochika Okahashi, Honorary Chairman of Seiko Forestry and Shigenori Tani, President of Tani Forestry. Both were born into families of hereditary Yoshino forest owners, have witnessed the transformation of Yoshino Forestry firsthand, and are now exploring new models for the industry. We asked them about the future of forestry from the perspective of the contemporary forest owner. The two of you are what are known as Yamadanna (another term for forest owner). What generation are you, respectively? Mr. Okahashi: My family has been engaged as forest owners since the mid-Edo period (around the 18th century), and I am the 17th generation. Our ancestors served as village headmen in what is now Kashihara City, Nara Prefecture (formerly Magata Village) and were large landlords who leased out about 70 hectares of land to tenant farmers. In my father’s generation, forestry was the main livelihood, and the Yamamori (forest custodian) System was already well-established. We had 66 Yamamori managing the mountains on behalf of the owner. A chief Yamamori (Shutto) acted as the head clerk (Obangashira) managing the forestry operations. My father reportedly only visited the mountain twice in his entire life. Forest owners did not directly intervene in day-to-day management. In 1950, we founded Seiko Forestry, and began owning and managing part of the forests as a corporation, and fully developed our forestry business. This year marks our 73rd anniversary. [caption id="attachment_5381" align="alignnone" width="2560"] Seiko Forestry — Honorary Executive Director, Kiyochika Okahashi (hereafter “Okahashi”)[/caption] Mr. Tani: My family began managing forests in the late Edo period (early 19th century) around present-day Oji Town in Kitakatsuragi District, Nara Prefecture, and later expanded into the Yoshino region. My father is the 13th generation, making me the 14th. Tani Forestry owns and manages about 1,500 hectares of forest, mainly in the Yoshino region. We are also promoting the spread of woody biomass infrastructure by holding events at our local woodland called “Youraku no Mori” in Oji Town, and selling firewood boilers and stoves. We are involved in various ventures to add value to forests and forestry, such as operating a hot spring facility that uses a firewood boiler in Tenkawa Village, Nara Prefecture. Actually, the Tani and Okahashi families are connected by a long history. Our great-grandmother's marriage from the Okahashi family to the Tani family was the catalyst. We've heard that our great-grandfather was inspired by his wife's home—the Okahashi family—and used them as a model to greatly expand our forestry operations. [caption id="attachment_5384" align="alignnone" width="2560"] Tani Forestry — President, Shigenori Tani (hereafter “Tani”)[/caption] Could you explain what the Yamamori (forest custodian) System in the Yoshino region is? Mr. Okahashi: The history of Yoshino forestry goes back to the Muromachi period (1336–1573), roughly 500–550 years ago. Planting became widespread around the mid-Edo period (18th century). To secure funds for maintaining the mountains, the ground rights to the planted mountains were sold to the wealthy, raising capital from within the prefecture as well as from Wakayama, Osaka, and Kyoto. These wealthy individuals were "investing," anticipating income when the trees could finally be sold. Since many of these investors lived far from the forests and could not manage them directly, they entrusted the management to trusted local people. This was the beginning of the Yamamori (forest custodian) System. The forest custodians managed the mountains on behalf of owners and earned a living from a 3–5% commission of the timber sales paid by the owner. The owners did not have to pay a monthly wage because they were not employing the forest custodians. It was convenient for both the owners and the Yamamori to wait until the wood sold for a high price, making this system a perfect match for the long-rotation period for growing trees and long-term investment. Thanks to this system, Yoshino’s villages prospered. Because the owners would invest again if a seedling was planted, trees were planted right up to the ridgelines in Kawakami Village. Thinned logs about 10 years after planting, called Tabanegi (bundled logs), were used for the decorative Saobuchi ceilings in Sukiya-zukuri (a delicate, traditional architectural style seen in tea rooms). Thin logs just under two meters long could be carried out by women, and slightly larger ones were used for rice-drying racks (hazakake-bō) or scaffolding. Even thinnings were profitable. I believe the economic advantage was one reason for the dense planting in the Yoshino region. The Yamamori System made Kawakami Village one of the wealthiest villages in Japan back then. If forest owners are essentially investors, it’s hard to picture them working on site. Mr. Okahashi, what inspired you to enter the mountains yourself? Mr. Okahashi: I got involved in forestry in 1974. At the time, helicopter logging was the norm in the Yoshino region, and transportation costs were enormous. After graduating from university and studying modern forestry with large machinery at a company in Gifu, I decided to apply modern forestry in my own forest holdings in the Yoshino region, riding the forestry boom. There was a strong momentum among young forest owners in their twenties to discuss and revitalize forestry, leading to forestry research groups and study groups on forest roads and logging trails. However, the Yoshino region was still quite closed off then, and the owners couldn't even enter the mountains without Yamamori's permission. I was young, and I didn't fully appreciate the Yamamori System (bitter smile). I had a university professor specializing in forestry engineering, who often visited the Gifu forestry company, drew up a plan for a logging trail to extract felled timber. I hired a contractor to build a 3.5–4m wide trail in my under-managed forest in Kamikitayama Village. But the further we went, the more the trail collapsed. The large-scale road construction method typical of modern forestry that worked in Gifu Prefecture's forests was unsuited to the soil quality and steep slopes of southern Nara Prefecture. Since the owners almost never entered the mountains themselves back then, I was heavily criticized behind my back by the forest custodian as "Bon-san's (young heir's) playtime." Mr. Tani: I had heard about Chairman Okahashi's long-term work on logging trails from my father and the forest custodian. When I first got involved in forestry, one forest custodian told me, "Don't be “a boss” like Mr. Okahashi, the president (at the time). A Yamadanna (owner) must be a master who takes a broad view. If you roll down the mountain and die, you'll incur inheritance tax and cause trouble for all the forest custodians and employees. Your father is the ideal master. Don't do unnecessary things." Mr. Okahashi: Later, I heard a rumor about a man building a logging trail by himself on the steep western slope of Mt. Katsuragi, on the border of Nara and Osaka prefectures. I visited him to see his mountain. That was my future mentor, Keizaburo Ohashi Sensei, a respected forestry instructor. He initially refused to show me his mountain, saying, "There's no point in looking at my mountain." However, I met him again when he was a lecturer at a silviculture training session at the Forestry Experiment Station (now the Nara Forest Research Institute). I told him about my failed attempt to build a logging trail in Kamikitayama Village. He asked me, "What are you going to do about that destroyed trail?" When I replied, "I guess I'll have to leave the destroyed trail alone," he snapped, "I won't teach anyone who is that irresponsible!" He said he would teach me if I fixed the destroyed trail myself, and invited me to a 10-day practical training session in Nishiyoshino Village (now Gojo City) the following year. After that, I invited Ohashi Sensei to my mountain in Kamikitayama Village, and we spent six months fixing the destroyed trail. Then, in 1981, we started building logging trails ourselves. Ohashi Sensei's philosophy was simple and clear: "Build a road, and get the timber out cheaply." The trails we built, utilizing the natural terrain, were 2.5m wide—enough for a 2-ton truck—and were designed not to destroy the mountain. Believing that this trail construction was essential for Japanese forestry, I followed him as his apprentice, traveling across Japan—from Hokkaido Prefecture in the north to Kagoshima Prefecture in the south—for lectures and surveys. Eventually, I, too, began practically teaching logging trail construction in various locations.The hardest part of building a logging trail is deciding where to put the path. You must first study topographical maps and aerial photos, understand the mountain's formation, and then enter the mountain. You need to determine where to place switchbacks to gain elevation and which of the many valleys can be crossed. You walk, mark the spots, and finally connect it into a single road. Ohashi Sensei always told me, “Walk the mountain and listen to its voice.” During the 2011 Kii Peninsula floods—a massive rain disaster centered on Wakayama, Nara, and Mie prefectures—many mountains collapsed, however, none of the trails built according to Ohashi Sensei's teachings collapsed. Since then, these logging trails have been widely adopted across Nara Prefecture under the name "Nara-type Logging Trail." [caption id="attachment_5396" align="alignnone" width="2560"] A logging trail of about 2.5 meters wide built by Mr. Okahashi[/caption] [caption id="attachment_5389" align="alignnone" width="738"] An explanatory panel about Mr. Ohashi’s trail method at the trailhead[/caption] Mr. Tani, why did you decide to start going into the mountains yourself? Mr. Tani: For someone with a privileged upbringing like me, I never thought I could take on dangerous forestry work. Still, perhaps somewhere in my heart, I had always yearned for the world of forestry that surrounded me as a child. I began to admire cool foresters like Chairman Okahashi, who worked on logging trails, and the forest custodians who were engaged in mountain work. In my twenties, while taking over the family business, I acquired qualifications like Real Estate Transaction Specialist and Tax Accountant to stabilize the family's financial foundation. At the same time I joined a forestry course in Mie Prefecture as one of the steps to prepare for entering the business. Once the financial reconstruction was somewhat on track, I seriously began engaging in forestry. This timing coincided with a period when other Yoshino forest owners of my generation were also taking over their parents' forests, which gave me a sense of hope and security that I had like-minded forestry colleagues around me. I started with brushing and thinning in the Yoshino region, and eventually took on logging trail construction and raw material production. I believe the presence of friends I met at forestry school and the strong support from Chairman Okahashi allowed me to take the plunge into forestry. In 2011, when we built a logging trail in my forest in Oji Town, Mr. Okahashi helped with everything—from arranging the purchase of a Yumbo (hydraulic excavator) to route surveys and technical guidance. Whenever something went wrong—nearly tipping the machine or cutting a water pipe—I called him. (laughs) I am truly grateful that he always helped me without showing any sign of displeasure. Furthermore, a young employee from Tani Forestry was allowed to train at Seiko Forestry for a year on logging trail construction. That employee is now entrusted with supervising the logging trail construction sites. [caption id="attachment_5390" align="alignnone" width="749"] Trail-building in progress[/caption] Do you also support other people working in forestry within the prefecture? Mr. Okahashi: I’m mostly retired now, but my younger brother provides instruction on logging trail construction. People come from all over Japan to train with great enthusiasm. Some put down roots in Yoshino and continue forestry, while others return to their hometowns to build logging trails there. Mr. Tani: Around 2010, forestry began to gain momentum with the promotion of the Forestry and Forest Industry Revitalization Plan*, which led to more opportunities for young people to gather. Chairman Okahashi was consulted as an expert on logging trails to provide policy recommendations for this plan. While my company is engaged in logging trail construction and timber production, I want to create a better support system for people involved in forestry. For example, many people say, "I can't manage the forest I inherited from my parents, so I want to let it go." I want to use the knowledge from the qualifications I acquired while stabilizing the family's finances to create a system that broadly supports people facing similar difficulties, not just in terms of tax and registration, but also in forest sales. Although this is still in the foundational stage, I believe such a system is necessary in areas without a forestry cooperative, like Oji Town. I'm also slowly thinking about rebuilding the network that the forest custodians used to maintain in their communities. *Forestry and Forest Industry Revitalization Plan — A national plan formulated by Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries in 2009 under the slogan “From a Concrete Society to a Wooden Society,” aiming to revitalize the country’s forests and the forestry industry. What challenges have you noticed or felt in forestry through your activities? Mr. Okahashi: I feel that forestry is less profitable now than in the past. The first problem is wildlife damage. Even with netting, deer jump over it, and planted seedlings are all eaten. The deer population must be controlled, but there's a sense that it may be too late, and it is having a considerable impact on the ecosystem and natural environment. In the past, the severity of winters and food shortages naturally culled populations, but with the extinction of wolves, global warming, depopulation, and the aging of hunters, a large number of deer can now survive. Even with government subsidies for tree planting, conditions are tough. Mr. Tani: The shortage of successors to the forest custodians, who were the backbone of Yoshino Forestry, and the general lack of young forestry workers are major issues. Former Yoshino Forestry thrived because of the forest custodians. I hear that the forest custodians were exceptionally talented managers who utilized their community base in the remote Kawakami Village to understand the timber demand in major cities like Kyoto and Osaka, and developed the timber transportation infrastructure via the Yoshino River's channel improvement, establishing the management foundation for Yoshino Forestry. It is extremely difficult to nurture successors with such excellent management perspectives, but we are experimenting daily to find a mechanism to cultivate such human resources. How do you think these challenges should be addressed, and what is your outlook for the future of forestry? Mr. Tani: The revival of forestry is a very challenging theme, so we must explore various approaches. Currently, we are challenging ourselves with new initiatives to add value to forests, such as creating forest absorption credits through the J-Credit Scheme* with several forest owners. We want to create model cases that resonate with and contribute to a decarbonized and biodiverse society, and use the resulting economic value to reinvest in forestry, leading to a sustainable cycle. In November 2023, a forest I own—Youraku no Mori, where I built my first work road under Mr. Okahashi’s guidance—was certified as a “Nature Symbiosis Site*” by Japan’s Ministry of the Environment. From 2014 to 2016, we hosted a two-day event there called “Chime-Ringing Forest” that attracted over 5,000 visitors each year. The forest is a place for exchange, not only for locals but for many people, serving as a location for activities by the organization for people with disabilities "Nanairo Circus-dan" and for nature observation gatherings led by a local insect ecology photographer. *J-Credit Scheme — A government certification program that recognizes the amount of greenhouse gases reduced or absorbed through initiatives such as energy-saving measures or forest management as “credits.” These credits can be used to promote a company’s commitment to climate action or sold to other organizations, generating revenue that can be reinvested in further environmental efforts. *Nature Symbiosis Site — A certification program launched by Japan’s Ministry of the Environment in fiscal year 2023.It recognizes privately managed areas—such as corporate forests, satoyama landscapes, and urban green spaces—that contribute to biodiversity conservation. As of February 2024, 185 sites have been certified nationwide. [caption id="attachment_5392" align="alignnone" width="563"] Crowds at “Chime-Ringing Forest”[/caption] [caption id="attachment_5391" align="alignnone" width="727"] Members of NPO "Nanairo Circus-dan"[/caption] [caption id="attachment_5393" align="alignnone" width="587"] Mr. Tani receiving the Nature Symbiosis Site certificate[/caption] Mr. Tani: I hope that forestry becomes an appealing profession that attracts more people to the industry. To achieve that, I plan to re-implement the lessons I learned from Mr. Okahashi. We are planning to build visitor-attracting facilities, such as a bakery and café, at Youraku no Mori, using timber we cut and mill ourselves. Both the owners and the forest custodians have a strong desire to revitalize the current state of forestry, so I hope our work can serve as a model case and attract more colleagues. Mr. Okahashi: The solutions boil down to two things: buying timber at stable prices and using timber steadily. If we don’t consciously use local wood, our forests will deteriorate. The biggest demand driver is construction—closely tied to everyday life. With advances in technology in recent years, not only detached houses but also mid- to high-rise buildings, condominiums, and apartments can be built with wood. If we increasingly use local wood in such construction, the demand for timber will rise. If the price of wood stabilizes, everyone will work hard to plant trees. If that happens, measures against animal damage will also progress. When the price of wood doesn't go up, we lose the energy to find those creative solutions. I would be delighted to see more architecture in the world built with "Japanese wood." Mr. Okahashi, who established the "Nara-type Logging Trail" by personally entering the mountains—a rare act for a Yamanushi in his era—and implementing logging trail construction suited to the Nara region's terrain. And Mr. Tani, who inherited Mr. Okahashi's teachings and is undertaking various new projects to expand the possibilities of forestry. Both men have sought the ideal future for forestry through their respective activities. Their strong desire to protect the beautiful forests inherited as owners and revive forestry as a sustainable industry is palpable. They also possess a unique, deep commitment to mountain preservation, having grown up watching the people who protected the mountains from a young age. What is necessary to pass on our beautiful mountains to the next generation? Perhaps it is for each of us to put ourselves in the shoes of the owners and forest custodian and consider the fate of our local forests. Information Seiko Forestry(Head Office) 9F Seiko Building, 2-2-20 Saiwaicho, Naniwa-ku, Osaka City, Osaka Prefecture(Branch Office) 701 Iinari, Yoshino Town, Yoshino County, Nara PrefectureURL:http://www.seiko-forestry.co.jp/ Tani Forestry2-16-36 Motomachi, Oji Town, Kitakatsuragi District, Nara Prefecture

2026.01.22